When expanding your SaaS company, don’t enter the Suicide Quadrant.

Why not?

First of all, let me explain.

I’m referring to a quadrant in the Ansoff Matrix, a commonly taught framework in business school to visualize growth opportunities. It was developed by applied mathematician H. Igor Ansoff and published in the Harvard Business Review in 1957.

In the 2X2 matrix, featuring New and Existing Products on the x-axis, and New and Existing Markets on the y-axis.

What makes it useful for growth strategy is the classification of relative risk:

The “Diversification” quadrant is sometimes known as the “Suicide Quadrant” because of the low probability of success (AIM Institute research puts the chances as low as 5%).

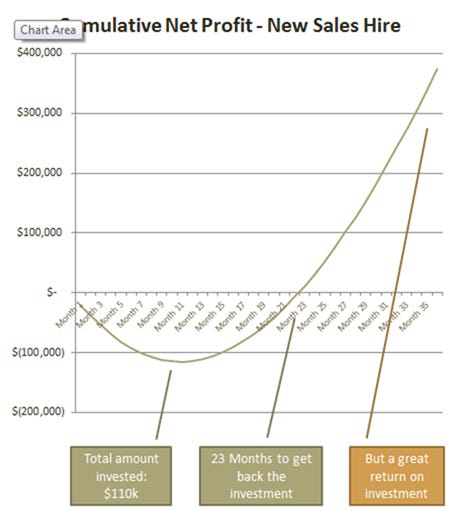

Expanding into new markets typically involves elevated levels of investment, with uncertain time horizons for returns.

Building new products typically involves elevated levels of investment, with uncertain time horizons for returns.

Taking on both at the same time increases risk exponentially, and while the potential rewards are also enormous, given that the time horizon has compounded uncertainty it is very likely that a SaaS startup will have to burn cash for an indefinite amount of time before seeing returns.

Even without these dynamics, David Skok documents the economics of SaaS as having a 23-month cash flow trough due to having to invest upfront in sales and marketing expenses to acquire customers, and only get payments from those customers over a delayed period of time.

At EngageRocket, we’ve always sold annual contracts with payment upfront to mitigate the effects of the cash flow trough. But as any founder who has struggled to find Product-Market Fit, living in the Suicide Quadrant is bad news. Usually, the only companies operating in that quadrant are those already established and with large cash reserves: eg Apple introducing the Vision Pro to enter the AR market, Google entering the smartphone market with the Pixel or Elon buying Twitter.

OR they are new startups that have to raise venture capital to fund both market and product development.

Without these reserves, risks of operating in the Suicide Quadrant are:

❌ Getting spread too thin and losing focus

❌ Becoming too complex and dramatically increase management overheads

❌ Increasing inefficiency because processes are much more opaque

I stumbled into the Suicide Quadrant and nearly tore the company apart

In the fog of war, it’s easy to forget basic business school tenets like the Ansoff Matrix.

When we decided that EngageRocket would formally try to figure out the US market, there was a lot of residual fear.

Fear that our product development was lagging behind our competitors who have raised 50X more funding.

Fear that our go-to-market strategies would not be able to withstand the heat of competition in an unfamiliar market.

Fear that we wouldn’t be able to adequately serve a market that has a higher level of SaaS and HR maturity.

In hindsight, I fed these fears even more when we attended tech conferences to get a sense of the market and tailor our entry strategy.

I forgot the fundamental truth that people who go to tech and HR tech conferences are far from representative of the whole market.

I also made the mistake of thinking that the 600,000+ companies within our TAM were homogenous.

And so I was convinced that we needed new product development to differentiate and meaningfully penetrate the US market. Mistake #1.

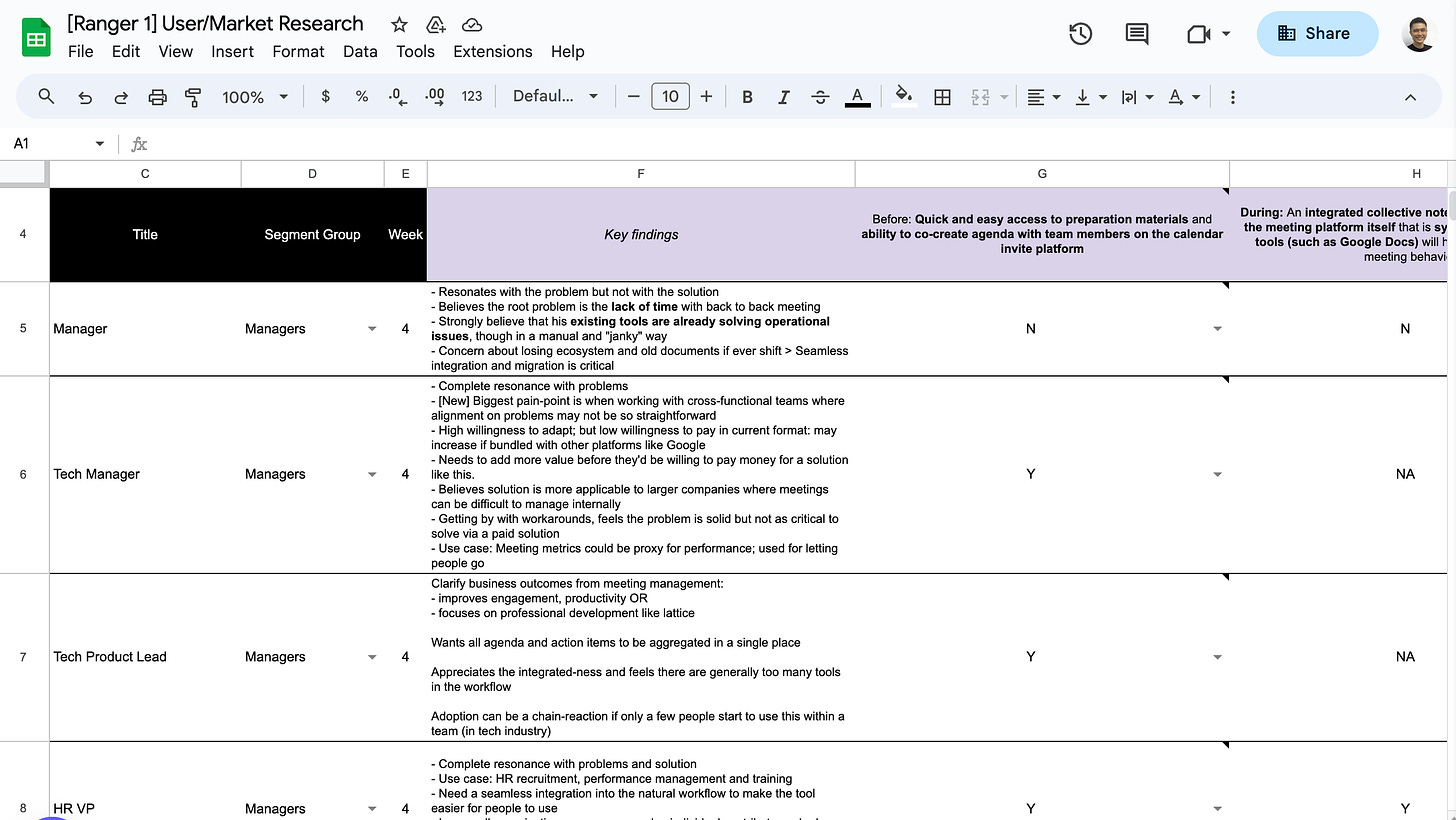

With the confidence of a 2nd-time founder, I expertly applied a robust Customer Development process and successfully managed to connect with a swath of different user personas. 30+ interviews later, we had a solid database of insights, carefully iterated at every stage:

While our starting persona was people managers in an organization, the resultant persona with the greatest pain for what we thought we could build to solve was…

Project managers. 🤦♂️ Mistake #2. (Our core persona for our existing products was Chief People Officers)

To top things off, I extended the need to increase monthly / weekly active usage in order to improve retention rates in a competitive market. This led to the conclusion that we should attempt a Product-led Growth (PLG) motion to enter the US market. Mistake #3. (No one on our team has successfully implemented PLG at that time)

Not only were we attempting to enter a new market. Under this plan, we were going to do so with an entirely different Ideal Customer Profile (ICP). With an entirely unfamiliar GTM motion.

Of course, when you put it that way…

While eventually these errors resulted in some breakthrough innovation (the source of another post), they also cost us:

$100K+ cash burned

4+ months of time

A lot of emotional distress from differing priorities between regions

With little to show for it except a lot of documentation and prototype screens.

Which is why I want to share this with you.

Tackle one quadrant of the Ansoff Matrix at a time

If I could go back in time, knowing that we had to enter a new geographical market, I would have kept everything else as similar as possible to our known operating environment.

✅ We were familiar with HR as our ICP.

→ We should have continued to sell to HR.

✅ We were familiar with a top-down sales process.

→ We should have continued with a top-down sales process.

✅ We were familiar with the buying process of mid-sized companies.

→ We should have continued selling to mid-sized companies.

Two months ago, we made the decision to collapse our ICP across all regions.

While it was difficult, we did eventually find that it was possible. The 600,000+ company TAM in the US was actually made out of many different sub-segments of the market. Which we could identify and target once we escaped from the lure of tech events.

It’s still early days but:

Product development has never been clearer. We now have a high-conviction roadmap spanning almost 12 months.

GTM activity is picking up and gaining focus as we can pitch to solve similar pain points across all markets with a common ICP.

Team alignment within the company is a lot clearer, causing less stress from conflicting priorities (though there’s still high levels of stress from the need to execute quickly).

I wish I had read a post like this before charging into the Suicide Quadrant. Thankfully we pulled out just in time to course correct, and glean some valuable lessons and a lucky product breakthrough.

That’s why it mattered so much to me to write this post. When thinking about expansion:

Founders, choose your quadrant wisely.

Product & Growth leaders, make sure only one of you goes out on a limb at one time (unless you’re Apple and sitting on mountains of cash).

Investors, advise your portfolio companies to assess these risks thoroughly.

Startups are all about facing risks. But it’s our job to make sure that we’re not taking unnecessary ones.

This Substack is where I write about our experience expanding from a stable, growing market in Asia, to competing in the largest SaaS market in the world.

We’d like to invite you to join us on this adventure by subscribing:

What to expect?

📊 Comparative Data Analysis: Deep dives into metrics and strategies, comparing and contrasting SaaS practices between East and West.

🎙 Podcasts: Candid chats with industry leaders, unveiling the challenges and triumphs of the startup journey.

🎤 Exclusive Interviews: Conversations with SaaS pioneers and innovators, sharing their unique insights and visions.

✍️ Opinion Pieces: My take on trends, disruptions, and the future of tech in these dynamic regions.

Who's this for?

• Founders seeking strategies and stories from dual perspectives.

• Investors eager for a fresh, grounded take on the evolving SaaS landscape.

• Tech enthusiasts, analysts, or anyone curious about the heartbeat of startup ecosystems in both the East and West.

Thanks for reading and do share with someone you think could benefit from it!